Cora Young is an atmospheric and analytical environmental chemist from York University in Toronto. Chemical and News Engineering Magazine has named her to the Talented 12 list, which recognizes up-and-coming chemistry researchers and innovators who are tackling some of the world’s most pressing issues.

Cora went to the Arctic on a scientific research trip to take samples and found forever chemicals PFAS (per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances) in the Arctic.

CFCs (Chlorofluorocarbons) as an aerosol propellant were banned when we discovered they were breaking apart our planet’s ozone layer, but they were replaced with other forever chemicals that can cause problems as well. These chemicals keep getting replaced again and again as we discover the damages they are causing.

Cora and Laura discuss ways to reduce using these forever chemicals in everyday items around our home.

Laura (33s):

Hello everyone. And welcome to the zero waste countdown podcast and radio show. We are speaking today with Cora young. She is an atmospheric and analytical environmental chemist from York university. The chemical and news engineering magazine has named her to the talented 12 list, which recognizes up and coming chemistry, researchers and innovators who are tracking some of the world’s most pressing issues. Cora, welcome to the show.

Cora (1m 1s):

Thank you for having me.

Laura (1m 2s):

I’m excited to talk to you about a lot of things today, actually, but first I want to know all about the talented 12. So what was that experience like? It seems like a pretty big honor.

Cora (1m 12s):

It was, it was a really big honor. I was nominated by two of my collaborators, which was an honor in itself and I was totally overwhelmed to make the list and yeah, I got to go to San Diego and meet with lots of prominent chemists and it was, it was a fabulous experience.

Laura (1m 31s):

Oh, that’s awesome. Were you nominated for like a particular study that you were doing or just like general your career?

Cora (1m 37s):

Some of my general work.

Laura (1m 38s):

Yeah. So what I really wanted to talk to you about say is some forever chemicals that you have been researching and you went up to the Arctic. So tell us about that. So first of all, I love the Arctic. I’m a little obsessed with it, but I’ve never been, so I, I want to know kind of all about it and what you doing up there.

Cora (2m 0s):

Yeah. So the Arctic is, is a really interesting place because it’s a pristine environment where we don’t have a lot of local emissions of pollutants. So anything that we find up there we know had to originate from somewhere else. So one of the things I find really interesting about the Arctic is understanding how chemicals get from where we emit them down here in lower latitudes, how they actually make it up to the Arctic cause once they get there, it’s a really cold environment.

Cora (2m 31s):

Of course, they end up trapped there and really polluting a pristine environment. Yeah. So we’ve talked a bit about like plastic being found in snow with samples up there, which is really disappointing.

Laura (2m 45s):

So what kind of things were you finding up there?

Cora (2m 47s):

Yeah, so we were looking for organic chemicals. We were looking for Per-fluoroalkyl substances or PFAS, which have come up in the news quite a bit. Recently we looked for PFAS actually amongst other types of chemicals, but we’ve been talking about PFAS a lot recently because our work was recently published on that topic. And so these are organic chemicals and they’re not really used in the Arctic they’re found in commercial products. So, and they’re hardly any people up there to use it. So we know that they must be getting there from, from our, from what sort of our environments, where we are using them.

Cora (3m 20s):

Yeah,

Laura (3m 25s):

Absolutely. And I wonder kind of how they’re getting up there. Well, do you have any theories on that?

Cora (3m 32s):

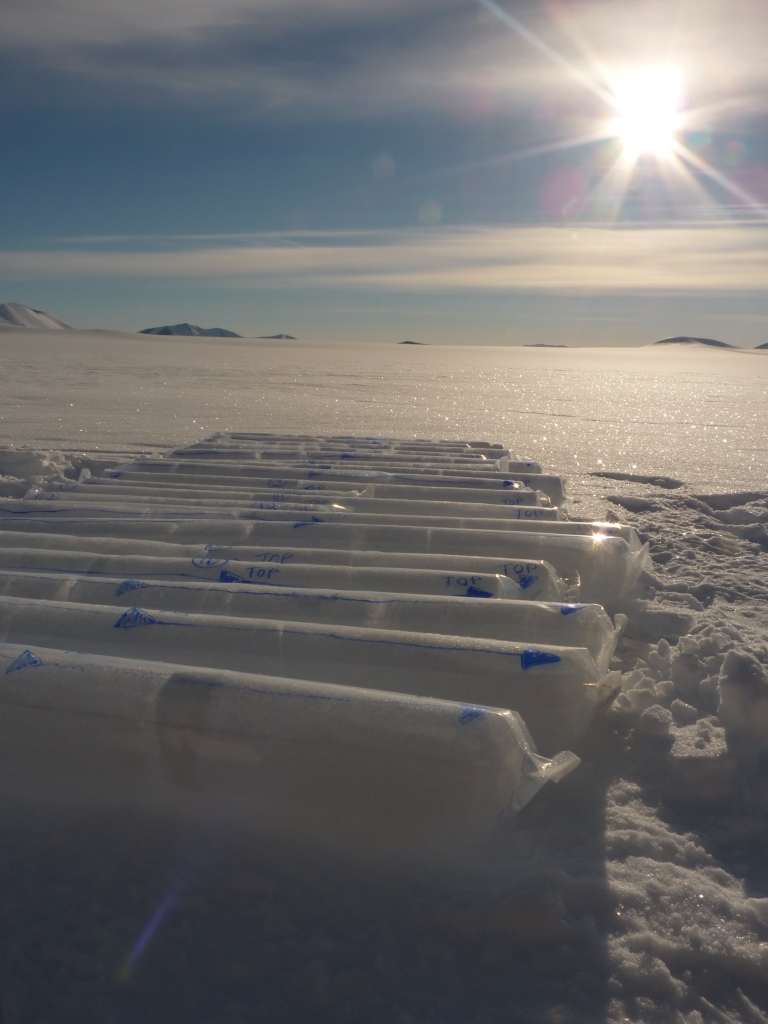

Yeah, so we were able to, to learn a little bit from our studies. So one of the things that we can do in the Arctic as well is collect ice cores. And so ice cores are really neat because they actually preserve a longterm record of the pollutant deposition. So you can think about it kind of like a tree rings, a tree rings where you can actually count back in time. And so by collecting an ice core, we can actually get the history of pollution that has arrived at the ice cap, single Pacers. And that’s really useful for helping us to figure out where these chemicals are coming from.

Cora (4m 4s):

And so some of these chemicals are well, they’re all being transported through the atmosphere really. And so that’s, that’s actually really useful if we want to do a better job of regulating it, regulating these chemicals.

Laura (4m 16s):

So an ice core is like going back in time a little bit, like what you said with the tree, right? You can, you can kind of look and say, okay, this was like a a hundred years ago. Like I’m not really quite sure. I think it’s the layering, right? Like each season layers different.

Cora (4m 31s):

Yeah, Exactly. So, yeah, they, it kind of, you can, if you look at an ice core, you can actually see the layers. So every, because it’s frozen, these layers actually are preserved. So, you know, one year snow will pile on top of the last year, snow and continuing and continuing on. And so from some ice caps, you can go back hundreds of thousands of years for our study. We’re really only interested in the past. We’re, we’re interested in a much shorter time span because of the types of questions we’re asking.

Cora (5m 2s):

So our ice cores were more on the 40 to 50 year, time span. Yeah.

Laura (5m 7s):

So you can tell when these things were laid down, but how do you tell, where are you looking at? Like, I don’t know if a volcano erupts, you might see some of that or something.

Cora (5m 20s):

So we kind of use environmental forensic techniques to try and figure out where, where these chemicals came from. So we can use something called air mass back trajectories. So that’s some modeling to figure out where air masses might’ve come from that might have delivered the chemicals. So that’s using a meteorology. We can also, we can look at the temporal trends. So we have, you know, 50 years worth of data so we can figure out, you know, say, Oh, the concentration started going up in 1990. So what was happening in 1990 that might have caused that to happen.

Cora (5m 54s):

We can look at the different, the ratios of the chemicals, interested to ratios of different things that we can understand. So it’s basically, it’s kind of like using a bunch of different environmental forensic techniques to figure out where the chemicals came from.

Laura (6m 9s):

That’s very cool. Well, it would be cooler if you weren’t finding like bad things, but it’s a very neat process. You were mentioning PFAS now I think PFAS were in the news a while ago because food companies were, I guess, putting it on paper to like make the paper hold liquid

Cora (6m 28s):

Yes. Liquid. Yes.

Laura (6m 31s):

We’re finding that. Like, it’s probably not very good for people and it’s a forever chemical. So like, besides the obvious, like are forever chemicals really forever. Like, do they go away and like, why are we calling them this?

Cora (6m 49s):

So forever is a relative thing. Yeah. I mean, no chemicals will be forever. I mean, eventually the earth will be engulfed by the sun. So, you know, forever it’s really meant on the timescale of, of, you know, our, our lives. So these chemicals will be around, you know, what, I’m gone when my kids are gone, when my grandkids are gone, they’re still going to be around. So it’s sort of on the timescale of a thousand years.

Laura\ (7m 13s):

Okay. Yeah. Yeah. And so why is PFS problematic? Like, that’s kind of all I know about it. Is there other things that you know about it?

Cora (7m 22s):

So it’s, they’re extremely persistent. So the fact that they are, these kind of forever chemicals is, is really a big problem. And, and one of the challenges with things that are forever chemicals that, that don’t break down in the environment is that we are committing ourselves to the pollution, right? So it’s, if we find out in five years that these chemicals are actually really toxic or they’re really terrible, or they kill frogs or, or something, then there’s no going back. So when we admit these, these chemicals that are forever, that are very persistent, we’re, we’re taking a risk.

Laura (7m 57s):

Yeah. Were there other chemicals that you found as well?

Cora (8m 0s):

We’re in the process of, of looking at other chemicals, but in these types of ice cores, we found we have in the past found things like flame, retardants and pesticides. So other chemicals that we are using in our daily lives also end up in the Arctic

Laura (8m 17s):

And how are these dangerous for the environment? Like, are they, do they accumulate an animals? Are there

Cora (8m 24s):

Really? Yeah. So PFS as well as some of these other chemicals, I’ve mentioned that they accumulate in animals there, they biomagnify, and that can be a real concern. So again, even if we, we don’t always understand what the health implications are for humans or animals right now, but because they are in the environment, they’re accumulating animals, they accumulate in us as well. And if we find out that there’s a really terrible, toxic effect, we’re going to be in trouble.

Laura (8m 55s):

Yeah. We had a scientist Come on the show a long time ago that that was studying microfibers and microplastic and like shrimp and stuff. And then he said that the one thing they found kind of the most of in the bottom of the ocean was Teflon. Yeah. Did you, did you find some of that too?

Cora (9m 18s):

So Teflon is one of the sources of PFAS actually. So PFAS is used in the production of Teflon. Yeah.

Laura (9m 27s):

Oh, okay. I didn’t know that.

Cora (9m 29s):

Yeah. So that’s related. Yep.

Laura (9m 32s):

Oh, okay. So is this why they go on our pans to make our pans nonstick? They have a similar thing to go on paper and make paper not get wet. I don’t know

Cora (9m 42s):

Exactly. Yeah. So it’s actually the chemical properties of PFS that makes it so useful. So basically PFS the properties, repel water, and also repel fats. So, you know, if you have Teflon coated khaki pants, then you know, if you spill olive oil on it, then it won’t immediately soak in and stay in your pants. You’ll have some time to wipe it up. Yeah.

Laura (10m 7s):

Where is it accumulating then? If not in the fat cause does doesn’t don’t things normally accumulate in fats? Like, is it a good,

Cora (10m 15s):

Yeah, that’s a great question. So PFAS does bioaccumulate and biomagnify but not the same as many other chemicals that, that bioaccumulate and biomagnify so as you said, yeah, that’s right. Most of them accumulate in fat, but PFAS actually tends to accumulate in blood. So it’s something that’s known as protein affiliates. So it’s tends to associate with proteins as opposed to fat. So it’s, it’s unique in that sense.

Laura (10m 40s):

Oh, that’s very interesting. That’s weird. Yeah. I’m just trying to think of the implications of like, if you’re giving blood or something and then you’re just giving people some

Cora (10m 49s):

Right. Well, I mean, it’s in everybody’s blood, unfortunately, so really? Yep. Yeah. Everyone has PAFS in their blood. So,

Laura (10m 58s):

And there’s not really a very many studies on like what it’s doing so much. Like it’s kind of a,

Cora (11m 3s):

There are, there are several studies. I mean, one of the challenges with understanding the impacts of these chemicals is that we’re all exposed to chronic we’re chronically exposed to low amounts and understanding the implications of that is much more challenging than if there was an acute toxic effect. Right. It’s not like if you’re exposed to P phos, you’re, you’re going to die tomorrow. It’s not what it’s not like arsenic or something like that. It’s, it’s more like a chronic low dose exposure. And it’s very difficult for us to actually understand that. If you think about how long it took for us to understand the negative impact of smoking, it’s kind of like that, except the effects can be even more subtle.

Laura (11m 41s):

Oh yeah. And you’d have to take a long time to do a study. And I think, you know, the studies are fairly short. I know there’s like the Harvard longevity study that’s like 70 years or something, but I don’t think many studies go that long. So exactly. Yeah. And did I read somewhere that these chemicals were replacing something else that was like bad for the environment?

Cora (12m 1s):

Right. So one of the things that came out of our most recent study was that the source of the PFS in the Arctic was actually from CFC replacements. So we obviously CFCs, we know destroys stratospheric ozone it’s very bad. And so we, we, as a, as a global community, came together to ban CFCs to protect the ozone layer, which was great. But we replaced our CFCs with other chemicals, which then degraded and their degradation products included some of these PFAS chemicals.

Cora (12m 33s):

And in our most recent study from the ice core, we learned that some of these CFC replacements were actually important sources of PFAS

Laura (12m 41s):

So if you’re listening and you maybe you’re like young and you don’t remember when this happened. I remember when it happened. Yeah. CFCs were a really bad thing. It was like, yeah, your hairspray is like killing the planet. Basically. Like every time you spray it, it’s basically like an aerosol, right. Is,

Cora (12m 59s):

Well, it was used as an aerosol propellant. Right. So that’s what it was. That was actually what was allowing your hairspray to come out. So CFCs were using lots of things. Air conditioning is one of them. So CFCs and the replacements are, are no longer used in hairspray most hairsprays anyway, but they are, I mean, they’re really important for air conditioning. And of course, you know, for many people that’s essential. And so we, we have to find alternative chemicals that we can use so that we can still have air conditioning.

Laura (13m 28s):

Oh, wow. I didn’t know that it was an air conditioning. That’s very interesting. Yeah. Because I was like one of the big kind of like cornerstones of development. I’ve read this, that so many people now have access to air conditioning. That it’s like a good thing. And you know, in the seventies, like hardly anyone did. And so now it’s just like pumping out this stuff. That’s maybe not good.

Cora (13m 49s):

That’s a challenge. Yeah. Because we want to, obviously we want to make sure we can still have air conditioning, but we want to minimize the impacts of the chemicals that we use to air condition. Yeah.

Laura (14m 0s):

Yeah. You know, it’s interesting talking about the trade offs, because we talked about this a lot with getting rid of plastic, like, okay, are you going to switch all of your plastic bags over to paper bags? And then just like cut down on your forest. Like sometimes we think we’re doing a good thing by getting rid of something or, or whatever. And then you see that it’s being replaced and I’ve read this about actually, my, my cousin’s a chemist. And he told me that BPA was with BPS. Yes. But it’s less studied and probably something similar.

Cora (14m 33s):

Yes. That’s, that’s a good example. And CFCs are kind of like that. So, you know, we, we keep, we replaced CFCs. We’re actually on the third generation now of CFC replacements because we replaced the CFCs. Then we find out that the replacement has an issue. Then we have to replace it again and again. And so, yeah. I mean, we’re, we’re, we’re trying to do better, but it’s, it’s hard to foresee all of the impacts of chemicals when we introduce them into the market.

Laura (14m 57s):

Right? Yeah, absolutely. And like you said, it takes some time, right? Like you might not see anything really bad about it until time goes on.

Cora (15m 5s):

Exactly.

Laura (17m 3s):

So I have, I have a weird question for you then. Cause I have like a dry shampoo spray that I don’t use very much, but it, it has like a spray function. So would that have like PFS in it as a propellant?

cora (17m 17s):

Well, it’s a CFC replacement, not necessarily. So one of the things that’s happened actually as we’ve banned CFCs and tried to replace them is we’ve actually found non fluorinated and chlorinated alternatives. So CFCs are chloroflurocarbons and it’s the fluorine and chlorine and the chlorofluorocarbons set are actually causing a lot of the problems. And so if we can make alternatives that don’t have the chlorine in the fluorine, then those can actually be very, can be much more, can be much greener. And so a lot of applications of CFCs have actually been replaced with non alternatives.

Laura (17m 52s):

So that’s good. So what might not be that bad? That’s right. Yeah. That’s good to know that because I was going to ask you like what, what can we do to avoid these chemicals? Like there, it’s not on my label of the dry shampoo, right? So how would I know?

Cora (18m 5s):

Well, and you know, Teflon is one of the things that’s that can be related to PFS and you can sometimes avoid it, but it’s a tough one also is in products and not always labeled, but that being said, Teflon’s not always a bad thing. And some of these products are very useful and you know, we want to, they certainly have a place in our lives. It’s it’s more about using them when they’re most essential. So I’m not saying we should ban air conditioning, we certainly need air conditioning, but there are certainly opportunities to reduce superfluous use, Let’s say, of some of these chemicals.

Laura (18m 40s):

Yeah. Or like when you put on the air conditioning and then like go get a sweater and like maybe turn it down a bit. Maybe. Exactly. Yes. Yes. I have a, I have a heat pump, so I didn’t want to go with the air conditioner. The heat pump was supposed to be better, but it uses a refrigerant. So I wonder what the refrigerant is. It’s going to be probably a CFC replacement. Yep. Hmm. Yeah. It’s actually broken right now. So I haven’t used it all summer. So I feel a little better in that case.

Laura (19m 12s):

Yeah. So I asked the last scientist, he talked about Teflon. If he thought it was getting into our water supply from like kind of everybody just using forks in their Teflon pans and then washing it down the drain. But I wonder if it’s like being dumped or if it’s just like getting in the air and then kind of raining down in the ocean. Like you guys have any idea of

Cora (19m 33s):

Well Teflon in a lot of things besides pants. I mean actually a lot of dental floss has a Teflon coating.

Laura (19m 39s):

No really that’s crazy.

Cora (19m 42s):

So it’s not always labeled, it’s not always obvious. So I, I think there are probably, I mean, it’s coming from all kinds of different products. I mean, you can get Catholic Teflon, coated, khaki pants. I wasn’t joking when I gave that example earlier. That’s a real product.

Laura (19m 57s):

Wow. Interesting. Yeah. The good for people working in like kitchens, I guess. I don’t know. Hmm. I don’t know. I’m really worried about the floss though. If you’re getting like chemicals in your blood, because you’re flossing. I use like a, a natural, Oh gosh. It’s like a silk thing. Yeah.

Cora (20m 15s):

So the silk ones are probably Teflon free. Yeah. But certainly some of them, some brands certainly contain Teflon and it’s not always easy to find out which ones do. That’s a bit of a challenge. Yeah.

Laura (20m 27s):

Do you know of any other products that we kind of use every day?

Cora (20m 30s):

Oh, that’s a good question. I mean, it’s mostly on, in, on textiles. So anything that claims to be stain repellent, we’ll have some sort of likely has some sort of PFS on it. And so, you know, anytime you would wash that, you’re likely releasing some of the, these chemicals into the environment.

Laura (20m 47s):

I wonder that’s like furniture and carpet and stuff.

Cora (20m 49s):

Yup. Includes those things. Yep. Certainly. And so actually one of the things you mentioned earlier was food, paper packaging. So a lot of fast food papers. Yeah. They use PFAS on them because that PFAS prevents the grease from coming through and getting your fingers all dirty. So that that’s another application that may or may not be avoidable.

Laura (21m 15s):

Yeah. I wonder if it’s cheap to use, like, and that’s why it’s on everything because like, you know, if McDonald’s is using it or something, just for an example, like with all their camper rappers, that’s like billions of rappers. So I don’t think you could put like bees wax on it. Like where would you ever get that much bees wax to do something natural?

Cora (21m 32s):

So it must be like, cost-effective I would think, I would guess so. You know, I’m not sure about that, but that seems reasonable. Yeah. Yeah. So let’s talk about you a little bit, so, okay. Let’s so what got you interested into studying these forever chemicals? You know, I became interested in them when I was an undergraduate student and it was actually learning about their presence in the Arctic and you know, I love polar bears and, and whales and seals and things.

Cora (22m 3s):

And so I was really upset that these chemicals were basically polluting these animals that live thousands of kilometers away from people using the chemicals. So I became really interested in learning how that happened. Yeah. It doesn’t seem fair that they have to deal with it when it’s. Yeah, of course. It’s the people too who live up there who don’t use the chemicals, but then become exposed. Yeah. That’s our thinking about too, is the communities as all right.

Laura (22m 27s):

Yeah. And they’re probably more, more dependent on like the sea life.

Cora (22m 33s):

Yes. It’s definitely an example of environmental injustice. Definitely.

Laura (22m 36s):

Oh yeah. That’s a good point. Yeah. So how long did you spend up there?

Cora (22m 44s):

When I went, I’ve only been once I went in 2006 and I was there for a couple of weeks and it was, I was there in may. I saw the eternal son and it was very cold. Oh yeah. It’s very confusing. When you wake up in the middle of the night, I kept thinking it was morning, but no, it was two o’clock in the way, two o’clock in the morning.

Laura (23m 6s):

So that’s crazy. It’d be very, very cool to see, I think, did you grow up on a ship or did you fly?

Cora (23m 10s):

We flew. So I actually went to an ice cap to collect something like an ice core, but it wasn’t a nice core at that time. So you can fly on a commercial plane to, I flew to resolute Bay, which is a community of about 200 people in the high Arctic. And then you have to take a private plane to take you to the ice cap and the plane itself has skis. So you land, it’s kind of like, looks like, kind of like a water plane, but you land on a makeshift runway on the ice cap.

Laura (23m 42s):

Wow. That’s very cool. That’s in Canada, right? Resolute Bay. Yep. Yep.

Cora (23m 46s):

Nice and Nunavut. I think it’s in Nunavut. Yes. Yeah. Yeah. That’s very cool. So this seems like you’re doing like a really awesome career. Do you have like things coming up next or is there something that you’re working on currently that you can tell us about I’m working on all kinds of things. So we’re still working on analyzing our ice cores. We try to collect a lot. So that’s cause every trip is very arduous as you might’ve guessed from what I just said. And I do a lot of air quality work as well. So I’m looking at wintertime air quality, trying to understand that winter is a big part of our Canadian life and air quality in the winter.

Cora (24m 23s):

Isn’t as well understood as summertime air quality. So that’s, that’s something that I’m really interested in as well.

Laura (24m 29s):

Oh, that’s interesting. Yeah, because a long time ago we used to get like a lot of smog warnings and stuff and yeah, it seems like we don’t anymore, which is kind of, yeah,

Cora (24m 37s):

We’re doing a lot better. And I mean, across Canada and the U S we’ve done a really good job of, and, and Europe as well, we’ve done a really good job of, of imposing regulations that have improved our air quality. But a lot of what we understand about air quality comes from our measurements in the summertime and wintertime is, you know, that’s half of the year and we can have poor air quality in the winter and it’s just not as well. Understood.

Laura (25m 3s):

Huh. That’s very interesting. Cool. I look forward to reading about that and that’ll be awesome. I love like I love Canadian things just because like a lot of things always seem to be like American focus. Cause there’s just so much bigger and it’s our neighbor, you know? So it’s nice to see Canadians studying Canada. I just really like it. If there are anyone out there who’s listening who is interested in science, do you have any advice for them? If they’re interested in like sustainability, like studies kind of like this one a little bit.

Cora (25m 38s):

So, I mean, there are lots of resources out there to learn more, but I also advocate for, you know, if there’s a scientist whose work you think is really interesting reach out to them. So, you know, we, I love hearing from people in the public if they want to. I love hearing from students who want to work with me and I know many scientists who are like that too, so reach out because you never know what opportunity might be lurking.

Laura (26m 4s):

Oh, that’s awesome. And just the last question, zero waste countdown show. Is there anything that you do in your own life to be sustainable or maybe do you go to your way to avoid some of these forever chemicals?

Cora (26m 18s):

Yeah. And so I’m very careful to avoid synthetic chemicals whenever I can. That’s one thing, I mean that that’s sustainability and also because I want to avoid my own exposure. So that’s something I definitely look out for. I’m a advocate of public transit and walking. I hardly ever drive. I am very careful to not take planes, I guess that was in my former life. Now I can’t go anywhere by playing, even If I wanted to. And I am a vegetarian and have been for 20 years.

Cora (26m 48s):

So I try my best.

Laura (26m 50s):

Yeah. It’s a interesting, you can do so many different things. And I think people get weirded out. Like if they’re like not a vegan or something and they feel bad about it, but they’re like, you know, they, maybe they never fly or they don’t even own a car. They don’t buy anything in plastic. Or, you know, maybe there is a vegan that buys lots of things in plastic. Like there’s just so many things we can do in so many combinations and exactly it’s our lives, right? Like not everyone, like I don’t live in Toronto. I can’t, I can walk to fields and stuff.

Laura (27m 24s):

So yeah. You know, every little thing helps and actually, you know, writing to your politicians is the number one thing we can do. So we should all do that. Yeah. Yeah. Awesome. Well, this has been great. It’s been so nice talking to you. So thank you for doing these studies are very important and it was definitely a pleasure.

Cora (27m 47s):

Same here. Thank you for having me.

Laura (27m 49s):

Awesome. That was Cora young. She’s an atmospheric and analytical environmental chemist from York university in Toronto. I wanted to look into the issue of PFS just a little bit more. So I looked up the American environmental protection agency website. So it’s epa.gov and there’s a little section on PFS in there. So I’m just gonna read this to you. Studies indicate that PFO and P F O S can cause reproductive and developmental liver and kidney and immunological effects in laboratory animals.

Laura (28m 23s):

Both chemicals have caused tumors and animal studies and the most consistent findings from human epidemiology studies are increased cholesterol levels among exposed populations with more limited findings related to infant birth weights effects on the immune system cancer for P FOA and thyroid hormone disruption for P F O S again, like Cora said, it’s not killing us directly, but there are some concerns about what it’s doing over at long term in our bodies.

Laura (28m 59s):

If you’re wondering why I would buy a can of dry shampoo when I always use a shampoo bars instead, and I’ve used shampoo bars now for years, I was traveling with a little vile of cornstarch that I would put on my roots when I wasn’t able to wash my hair very easily. And I wanted to see how the can of dry shampoo compared. And I definitely say the cornstarch works so much better. This dry shampoo spray can leave a residue.

Laura (29m 29s):

It smells very strong. And now I found out from Cora that there could be some very bad chemicals in the cans. So it was all around a bad decision to buy a can of dry shampoo. I still have the can it’s about half full, but I do like to try things before I dislike them. So I wanted to just give it a go and see how it compared to corn starch. And I would say that it doesn’t really cornstarch seemed to lighten my roots though. So if you have black hair, it might not work as well.

Laura (30m 0s):

If that’s kinda not the look you are going for, if you were participating in plastic free July this year, it’s a little more difficult with COVID restrictions, but with a little creativity, some trial and error of course, and some determination it’s certainly possible. I have a nice little over the shoulder cooler bag that I never leave the house without. I keep an ice pack in there that way I have a nice cold water bottle throughout the day, and I’m not tempted to buy a plastic bottle beverage and the hot, hot heat. And it was plus 35 degrees Celsius here the other day at my house in Canada.

Laura (30m 34s):

So we tend to get nine months of cold and then three months of unbearable heat here with a few weeks of grace period in between the spring and fall. So the cooler bag really helps during the hot months. And I keep some snacks in there as well. A favorite summertime stop at the ice cream shop is a nice zero waste treat for kids. If you’re on a road trip or cruising around town or looking for a reward to get the kids out of the house on a bike ride or a walk, a lot of places offer dairy free and vegan options now as well.

Laura (31m 5s):

We never get the cups and spoons, always the cones. So there’s zero waste and we make a firm decision on what flavor we want instead of using those little plastic single use testing spoons. If you’d like to support the show, there are several ways to do it and you can leave a review on Apple podcasts. That would be super, super helpful. You can follow the show’s Instagram zero underscore waste underscore at countdown, or you can find me on tic talk or subscribe to the YouTube channel, which doesn’t have many videos. It’s just the audio tracks of the podcast.

Laura (31m 36s):

Or if you want to reach out with a story idea, I love to hear from you. My email is laura@zerowastecountdown.com. And if you’d like to discuss anything on the show, you’re welcome to email me as well. Podbean has a reward button that you can click right in the app to sign up for a monthly donation as well. Even a few dollars is super, super helpful, and probably the easiest way to donate to the zero waste countdown initiative is to click the PayPal button on the bottom of the website. Zero-waste countdown.com. Every action you do counts.

Laura (32m 8s):

So thank you so much for listening. I really appreciate it. And I hope that you have a wonderful summer.